O’Ri-G’In Stories: Charles Victor O’Regan

Ireland has a rich cultural history in its own nation. Ancient kings, folklore and mythology, rebels, and even Irish culture in America all lend themselves to a reading of Ireland as a vast narrative of cultural pride. However, those familiar with Irish writing will often find a desire to place Irish history in a global context, arguing that its culture can be found in the most ancient of roots. One might think of a similar vein to 2002’s romcom My Big Fat Greek Wedding’s running gag that “I’ll show you any word comes from Greek.” Though we may laugh at such an attitude, this tone comes from a desire to take pride in one’s culture, especially those that are seen in less favorable lights. To take this into an Irish context, we have pulled an item from our archives.

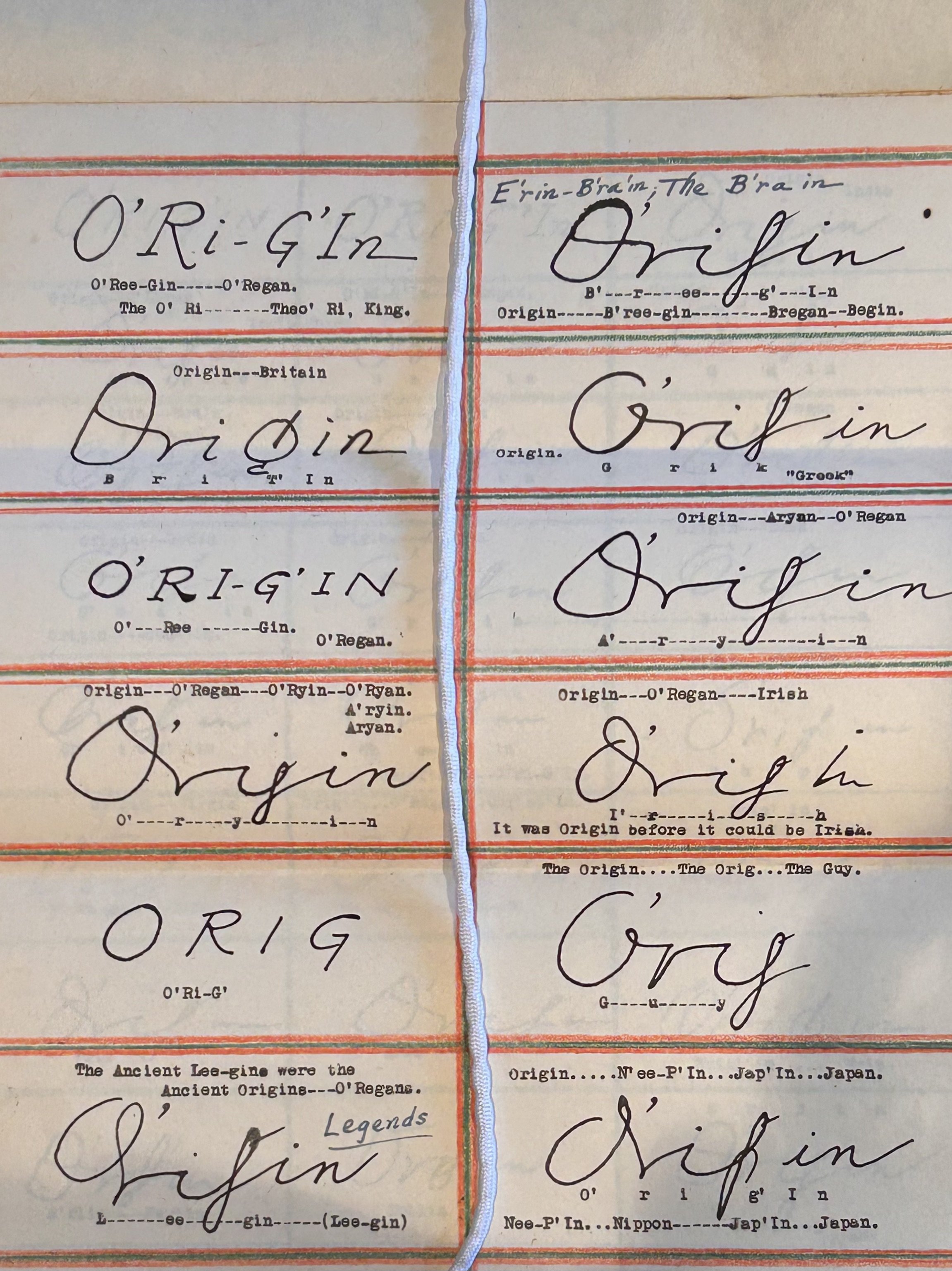

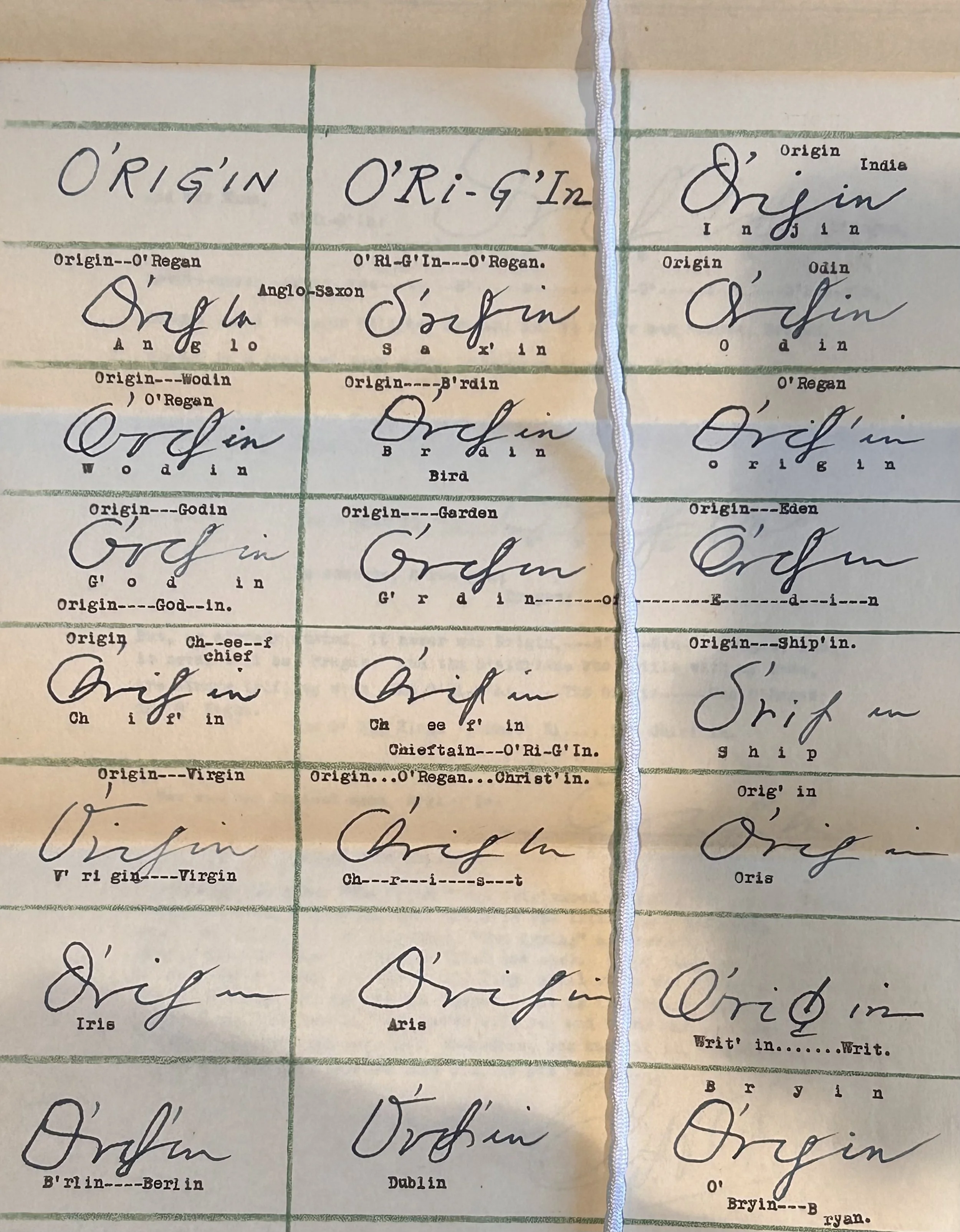

From our “crank letter” collection, we take a look this week at an etymological essay. Written by Charles Victor O’Ri-G’In (or O’Regan) and sent to us on 13 September, 1937, this letter goes through different spellings of the term Origin around the world and related terms. In doing so, O’Regan argues that each individual term can tie itself to the Irish surname. Such examples include “Ri” meaning “king” (in Irish), “Grik” meaning “Greek,” “Japan,” “Guy,” “Christian,” “Eden,” and “Aryan.”

Of course, there is a political component to tying oneself to these terms, especially to do so from a point of pride. There is a long history of Irish origins being tied to Christian and Greek stories, as a way to prove one’s worth in a Global context. However, given the dating of this letter to 1937, there are additional intentions that may come to light. This being said, given the collection it is featured in, we might take this as a more satirical piece. Throughout the piece, it comes off as a more poetic and often tongue-in-cheek tone.

Origin—first page

Origin—second page

Throughout this essay, O’Regan highlights various terms and writes them by hand with some etymological theory. His academic work is not necessarily the most accurate or clear, but as a satirical piece functions as somewhat comedic. For instance, he claims terms such as “Anglo-Saxon,” which clearly do not define Irish identity.

The piece is almost a work of poetry, making connections that don’t exactly follow through in clear etymological works. But by writing this piece, he traces his surname across the globe, calling himself—and his Irish kinsmen—a culture of value.