Archives Highlights: Robert Emmet’s Final Speech, Broadside - Part Two

The day before his execution, on September 20th 1803, Robert Emmet faced trial for High Treason.

The outcome was certain before the trial took place: an overwhelming amount of evidence had been gathered; Emmet’s defence attorney had been bribed by the Crown; and ultimately, Emmet refused to provide a defence, calling no witnesses to the stand.

The trial was, in many ways, a formality - but one which also provided Emmet with a platform. Facing his sentence, Emmet gave a final speech ‘from the dock’, in the courtroom.

AIHS’ copy of Robert Emmet’s final speech, published as a broadside in 1809.

The version above was published by The Aurora newspaper in Philadelphia, USA, in 1809 - with the accompanying claim that its first predecessor was “entirely spurious,” having been altered by the British Government to suppress Emmet’s eloquence and suit their own political agenda.

While the Aurora claims this is the most accurate version of the text, and harshly places blame on Irish newspapers for refusing to reproduce it, there are many reasons why these papers may have been hesitant.

Clipping from The Expositor in 1910 by Martin I. J. Griffin, alluding to the silence of Ireland being caused by British oppression.

Firstly, the political situation in Ireland may have caused Irish papers to hesitate. Following another failed attempt to overthrow the British Government, Emmet’s execution, beside seventeen other participants, had shaken the nation.

Secondly, without a reliable source - the Aurora lists their source simply as “a friend” - they may not have trusted that this version was entirely true.

In 1982, Norman Vance analyses the ‘most popular’ text, derived from the original court documents. Vance makes an opposing claim, that later versions of the speech (such as that produced by the Aurora), are the less accurate, with some quotes having been fabricated for the purpose of furthering the Irish Nationalist cause.

In Geoghan’s view, Vance’s suggestion is not an affront: part of the power of the speech comes from how it has been reproduced, edited, and circulated in different forms - the “truth” of the text is partly shaped by the purposes of memory and commemoration.

““What becomes clear is that the version of the speech that we use reflects the version of the truth that we want to project.””

In this way, it can be argued that The Aurora’s decision to publish Emmet’s “correct” speech gives a great insight into American sentiment towards Ireland, and its fight for nationalism and political independence.

The broadside’s titular engraving depicts a tomb to Robert Emmet.

In reality, no such tomb exists. Emmet’s remains were never claimed, leading to multiple sites around Ireland which claim to be his final resting place.

Famously, within this final speech, Emmet calls for no epitaph to be written in his name until Ireland gains independence:

“Let no man write my epitaph [...] and my tomb remain uninscribed [...]

When my country takes her place among the nations of the earth, then - and not til then - let my epitaph be written.”

The Aurora encouraged the memorialisation of Emmet’s final words, inspiring American support for the Irish struggle for independence. Using their platform to encourage American audiences to engage with the Irish fight for independence, this helped to cement Emmet as a martyr, gaining international support for the cause.

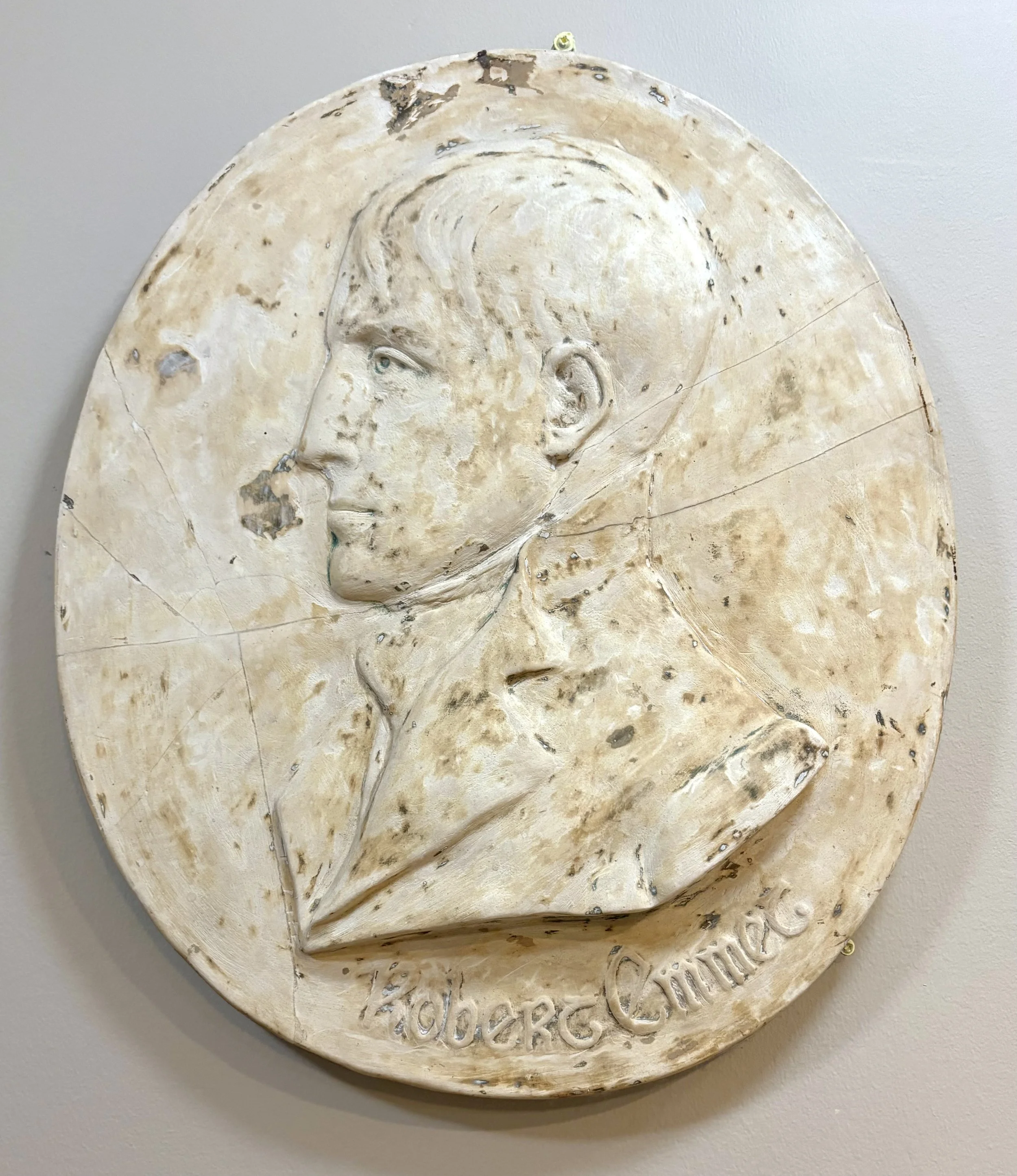

AIHS’ marble relief of Robert Emmet.